Paul Feig

The Rules of the Game

Woody Allen’s second film, Take the Money and Run, delighted a young Paul Feig. Even today it defines his sense of what you can get away with in comedy.

BY STEVE POND

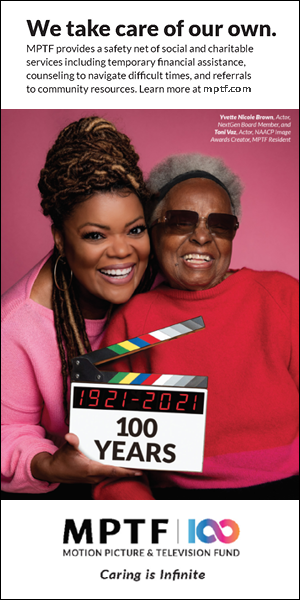

ABSURD: Feig (above) marvels at how Allen was

The first time Paul Feig saw a Woody Allen movie, he wasn’t looking for advice or inspiration to help him in a career as a comedy director. Instead, the 9-year-old Feig was simply going along with an older cousin who’d asked if he wanted to attend a double feature—which began with a thriller called W that scared him to death, then shifted gears to Allen’s Take the Money and Run. “It came on and it was like a religious experience,” remembers the director of Bridesmaids (2011), The Heat (2013), and the creator of the cult TV series Freaks and Geeks.

Feig considers the 1969 film Allen’s first as a director (He had made What’s Up, Tiger Lily? in 1966 by redubbing a Japanese spy picture.) A phony documentary about a hapless criminal named Virgil Starkwell, played by Allen, Take the Money and Run launched a directing career for the comic then better known as a standup comedian and playwright. It stunned the young Feig, a comedy buff whose exposure to the genre had consisted mostly of Warner Bros. cartoons and sitcoms like The Brady Bunch and Gilligan’s Island.

“I had never seen comedy like that,” Feig says as he prepares to watch the film in his Burbank office. “It was subversive and smart, and yet so silly at the same time. I wanted to be an actor at that point in my life, and when I realized that Allen wrote and directed and starred in this film, that really kind of set the course for what I thought my life was going to be.”The key, he said, was Allen’s balance of realism and absurdity. “As a director, you can put characters into absurd situations and even have them act absurdly without jumping the fence from having a base in human reality,” he says. “You have to create characters that we believe would do whatever extreme or absurd actions the story needs them to do, and you have to give them a specific set of rules they live by. And then you can take them into all sorts of craziness, as long as they are behaving according to those rules.”

The film starts with the portentous voice of a narrator, establishing the faux documentary format: “On December 1, 1935, Mrs. William Starkwell, the wife of a New Jersey handyman, gives birth to her first and only child.”

The grown-up Virgil Starkwell is introduced in a sequence in which he tries to play cello in a marching band, dragging a chair along with him and sitting only long enough to frantically saw at his instrument while the band stumbles around him. “This was the moment that so impressed me,” says Feig of the sequence, which is shot mostly by handheld, documentary-style shots from the midst of the band, along with a couple of wider shots. “Visually it’s hilarious, because there’s no way for the character to succeed, and it’s emotionally hilarious because you see him earnestly trying to do his best. It was the perfect way to show an earnest person up against the absurdity of life.”

But as much as the physical humor, Feig says he responded to the movie’s mixture of goofy sight gags—the blade of Virgil’s switchblade flying off the handle when he tries to open it—and jokes that reference psychiatry and literature. “It’s just gag after gag,” he says, “but I could never get over how he made even silly gags sound smart. Even if you didn’t get the references, you thought he was super smart. I wanted to be that smart and funny.”

Allen’s directing, Feig admits, is a work in progress. “This is definitely coming from his early days of standup and gag writing,” he says. “The movie is basically a joke fest. But what’s interesting to me is how in his career as a filmmaker he started to strive for more human emotion and storytelling, but never lost his love for jokes. As a filmmaker, over the course of decades you start to evolve and hit points where you want to experiment with different expressions of your voice. But the voice is always the same.”

SIGHT GAG: The character of Virgil Starkwell (Allen) is introduced playing a cello in a marching band. "It's visually hilarious because there's no way he can succeed."

After the escape fails, Virgil accepts an offer to try an experimental drug in return for parole, which turns out to have the side effect of turning him into a rabbi for several hours. “It’s so absurd, and yet played so real,” he says, as a bearded Starkwell explains the Talmud to prison guards.

Returning to the film, he laughs at a throwaway sight gag in which Virgil tips a maître d’ with a pile of coins he’d stolen by jimmying open a parking meter. “This got an enormous laugh in the theater,” says Feig. “But they blow through it. Don’t focus on it, don’t cut away to the joke. It’s that tossing off of comedy that is my personal key, and it’s done in a way I had never seen comedy done onscreen. Usually, comedy had a lot of energy behind it. This is so low-key. And low-key is such a funny way to do something so absurd—it helps sell the absurdity.” Underplaying, he adds, “is my favorite thing, especially from the actors around the stars. I’m always directing the one- or two-day people I work with to ‘Do less, do less, do less.’ Everybody wants to put too much mustard on the hot dog, if you will.”

The relationship sequence leads to Feig’s favorite part of the movie: an extended sequence in which Virgil tries to rob a bank by passing a note to the teller. But the teller has trouble reading the note, in which Virgil’s sloppy penmanship has made the phrases “act natural” and “I am pointing a gun at you” indecipherable. “That looks like ‘gub.’ That doesn’t look like ‘gun,’” insists the teller, who calls for his fellow employees to check out the note. The scene goes on for three minutes, the confusion escalating until an office full of employees is puzzling over the note.

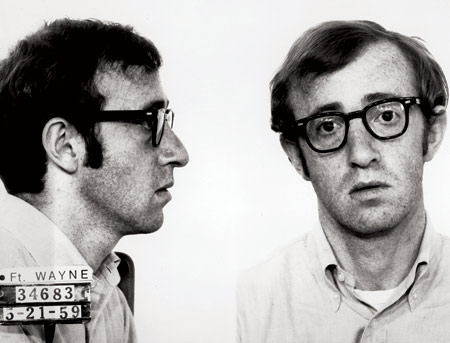

STICK 'EM UP:(above) Confusion escalates when a bank teller can't read a robbery note because of Starkwell's poor penmanship; (below) His parents are so ashamed of him after his arrest that they don fake noses and glasses for an interview

When Allen’s film cuts to interviews with Virgil’s parents, who are wearing fake noses and glasses because they are ashamed of their son, Feig says, “I have to think some of this was improvised. It’s sold so well if it’s not. It’s what I like to do; you can have a really well-written script, but I want the actors to make it their own, even if they’re just changing a word here or there. Just to make it sound like it’s the first time somebody’s saying it.”

One way Feig tries to get the improvisational feel is to shoot scenes over and over, which he admits is probably not a luxury Allen had on Take the Money and Run. “When I’m directing we always do a million takes, trying everything and changing stuff,” he says. “And I cross-shoot a lot, just so I can get that realistic feeling of hearing something for the first time. Nothing makes me more nervous than a really well-written, clever script. Because anything that reads so great like that, sounds written coming out of people’s mouths. I always hate when I feel like I can see the page as a scene is going on.”

But while Allen may not have been able to shoot endless takes, Feig figures that the freewheeling absurdity of Take the Money and Run probably means the director faced some of the same doubts on the set that Feig does. “I have to wonder what the crew thought about this movie when they were shooting,” he says, “because so many times you can tell the crew thinks you’re crazy. Generally, I’ve found that the take you want happens toward the end. But by then the crew has heard the joke a million times. They think you have it, and they think you’re just kind of screwing around or being obsessive.”

That, he insists, is far from the case. “It’s how it all cuts together. It’s like when the DP tries to talk me out of doing a close-up or getting coverage on a scene, because they’ve set up a great shot and think it should be a one-er. But I’m like, ‘You know what? You’re not going to be in the editing room where I need to have maximum freedom.’ Crews can get demoralized or a DP can get grouchy, but if an audience doesn’t laugh at a joke and I need to pull two seconds out of it to make it funny, then nobody gives a shit about how nice my shot is.”

Feig perks up at a sex scene in which Virgil’s horn-rimmed glasses somehow end up on Louise. “A sex scene in a comedy was just mind-blowing to me.” He marvels at a sight gag in which Allen tries to run down a woman who is blackmailing him by chasing her through her house in a rented car. And he gets excited by a scene in which Virgil plans a bank robbery by posing as a movie crew, complete with an appropriately-dressed German ex-con named Fritz as director. “Jodhpurs!” he says. “I wear a suit and tie when I direct, but I want to go back to the days when directors wore jodhpurs.”

As the credits roll, Feig says, “This wasn’t a tone I’d seen before. The old comedies I loved were very simple in their characters’ goals: The Three Stooges were always looking for a free meal; Laurel and Hardy were always trying to accomplish a task; The Marx Brothers were generally just trying to create anarchy. But Woody’s character had more complex goals. He wanted quick solutions to his problems, he had an ego, he made odd choices, he fancied himself a lover and he was a nerdy character who had no idea he was nerdy. His confidence was what made him unique. I’d never seen a guy who looked like him not portrayed as shy or awkward or nerdy, and that upended my idea about judging a book by its cover.” He shakes his head. “Woody really inspired so much of the way that I process stuff.”