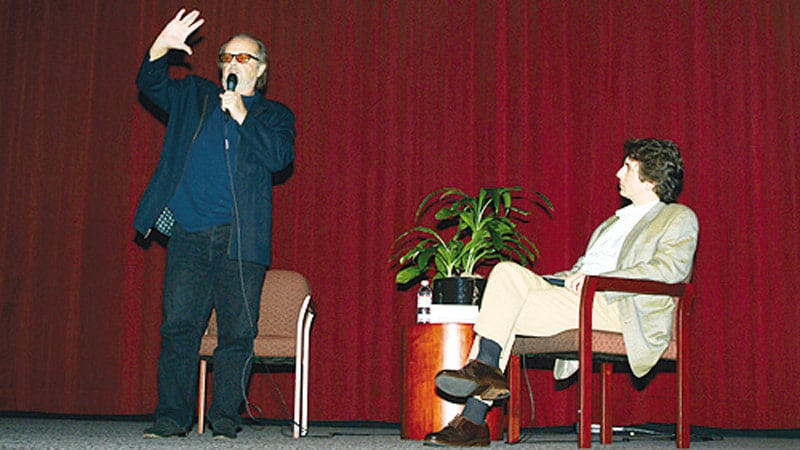

"The recent DGA Independent Directors Committee's (IDC) "Under the Influence" screening of Drive, He Said was a rare opportunity to spend some time with an undisputed icon, Jack Nicholson. What was refreshing about the evening was that members had a chance to listen to him talk about the less-glamorous beginnings and to be reminded that, though hard to believe, even Nicholson had to pave a way for himself.

Nicholson's involvement in indie films was more than 25 years ago, yet even his Academy Award-winning roles in As Good As It Gets, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and Terms of Endearment have not dampened his enthusiasm for indie filmmaking.

IDC Chair and DGA First Vice President Michael Apted noted that the idea for the "Under the Influence" series was born out of the Committee's desire "to try and remember why we're making movies in the first place." This takes the form of a director currently working in the independent world talking to a veteran filmmaker about a seminal piece of work that has inspired them. Director member Alexander Payne (Sideways, Election, Citizen Ruth) moderated the discussion with Nicholson. An interesting relationship because not only are they mentor/mentee, but they recently worked together on Payne's About Schmidt. Payne admitted he considers himself not only under the influence of '70s films but of Nicholson himself. "I was coming of age in the '70s," Payne said, "and one of the reasons I wanted to become a filmmaker is because I was watching your movies and all the great movies in the '70s."

"It was a golden age for moviemakers," Nicholson said. "I don't think anybody's ever had the kind of freedom that we had as moviemakers in the '70s. We were free to do whatever came into our heads. There was such a thing as an American film 'underground' that was quite extensive. It's been co-opted by the film schools now, but at the time there were a lot of extreme stylists working in it. And I remember a group of us, we were all cinefiles, we created a film society at a coffee house called The Unicorn."

Good films were shown there one night a week, according to Nicholson. "I've always said that the most interesting time period for me as a filmmaker was from about the beginning of the '60s well into the '70s. During those 10 to 16 years, you expected to see a masterpiece literally every week. I used to be able to say 35 Italian movie directors right off the top of my head that were working and had made good movies that we saw. This was the climate."

One of the reasons this climate no longer exists, Nicholson said, is that the stakes were different back then. "The distribution and cost situation was different so you didn't have to shoot for the bull's-eye. You could just make a film if you felt there was enough of an audience out there, and you could get by with a film that was pretty obscure."

Nicholson's career began to take off when he landed a job as writer for the Monkee's movie Head (1968) at BBS Productions. Formed by Bob Rafelson, Bert Schneider and Steve Blauner, BBS proved to be the spawning ground for an artistic renaissance in American filmmaking, producing such films as Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces, The Last Picture Show and the Academy Award-winning documentary Hearts and Minds.

Nicholson was to wear many hats at BBS, the most influential for him, of course, being that of actor. "I had been an actor for 12 or so years and I was in that familiar 'worst of all possible positions,' where everybody you speak with says you're wonderful — more than wonderful even — but you're not goin' anywhere. So you're worse off than somebody they don't even know."

Then came Easy Rider. It was the first and most successful film for BBS and not only made Nicholson an overnight star, but also widened the creative horizon for him. "I remember Easy Rider was originally going to be more a production job for me," Nicholson said. "When Bert asked, 'Could you play this part?' I said, 'A moron can play this part, Bert. A lot of people could play it a lot better than me, but if you're asking could I play this part, yeah, I can play this part.' I didn't know it would be as big as it was for me, naturally."

After the success of the film, Schneider gave Nicholson the chance to direct. "I was writing a lot and studying a lot and felt — as I do today — that I'll probably be one of the greatest directors that ever lived! By then there was no financial risk to letting me direct because they'd already made big hits. I felt I was a failed actor and wanted to direct."

Nicholson still speaks of Schneider with affection and respect. "Bert had a great movie feel. He's such an odd combination as a person. Very idealistic and, of course, very political. You know, it's one thing to say you're going to give somebody something; it's another thing to know exactly what it is they need to be given. And this is what Bert always knew. That's the kind of person he is."

Originally a novel by Jeremy Larner, Drive, He Said was brought to Nicholson by producer Fred Roos. "I connected with it because it was a basketball piece and it was an anti-war movie and had a lot of drugs and wild young people and excitement in it. It was a very lively thing, a very strong piece about what was actually happening in America at that time."

Nicholson said the University of Oregon was the only school that would let them shoot on campus. "The FBI subpoenaed our film because while we were shooting there was an actual student riot. Naturally, my group wouldn't let the FBI have the film. I think poor Harold [Gittes, co-producer] had to go to court for six years trying to deal with this."

Drive, He Said was the U.S. representative at Cannes '71. "And the first question asked of me as a director at this press conference was, 'Why should we be interested in this movie about all these schizophrenic people?'

"I looked out at this guy and I said, 'I'll tell you exactly why. Did you go to the lobster lunch at the Carlton today? And yesterday? And are you going to the champagne breakfast tomorrow morning here? You are, aren't you? Well, while we're doing this, there's a war going on in Vietnam in which these young people you see reacting strangely in this movie are going to have to fight. And I see a future where we're going to have to develop our ability to look at the world schizophrenically. As we have to be. Otherwise we'd be immobilized. I certainly wouldn't be here if I couldn't say, 'Well, I'm eatin' lobster, and these people I'm writing about are dying.'

"I thought it was a pretty good answer. But that was the times. And incidentally, there were riots at both screenings at Cannes — which didn't help the picture."

Nicholson told a story about how they skirted the law in order to get the last shot of the film where main character, Gabriel, goes crazy, runs around campus naked and has a field day in the science lab.

"We were allowed to have nudity in the picture," Nicholson recalled, "but we weren't allowed to shoot the actual nudity on campus. And in end where Gabriel is flipped out, I wanted a long sequence where he's driving himself crazy with drugs and, as you often do when you get too loaded, he's naked now. As far as I was concerned, we had to get this shot.

"So Harry [Gittes, co-producer], Fred Roos [associate producer], Steve Blauner [producer] and I, went out with Mike Margotta [actor playing Gabriel] nude and everything, Sunday morning when we didn't think anybody would be on campus. Fred went to one side of the lawn in a station wagon so he could pick Margotta up immediately after he made this [naked] run. And we were way over on the other side in order to take the camera, get outta there and get back to the hotel — and hope nobody saw us.

"Well, apparently somebody told on us because Margotta goes running like a son of a gun across the grass, and when he got up to the door, a guard appeared. So Fred got Margotta in the car and they went riding off one way. And we threw the camera in the station wagon and headed back to the hotel.

"So now we're all back at the hotel, hiding. And I didn't realize this 'til later, but we were a bit hysterical at this point. Because what I decided to do was, I'm in my hotel room and I know the police are coming. Blauner has got the film in the car and he's driving for the California border. Because, you know, I needed this shot.

"What I decided to do was I took off all my clothes, see, I decided that when the police came, I was going to greet them at the door naked. It seemed like a part of the piece to me, in a certain way but I also knew it would buy me time.

"And then here they came, the police. I open the door naked and they didn't say anything. I said, 'Yes, what is it?' They said, 'Well, there was a nude man...'

"I said, 'C'mon in fellas. Have a seat over here.' They came in, they sat down, and I said, 'Now, I just want to tell you there's no need for running around or investigations. Whatever this is, I am the responsible person and I'll tell ya everything about it, but I gotta wait for this one phone call from my partner. You can have a coffee. I'll put my pants on. Whatever you want.' Then, when Blauner got across the border, he called and I answered the phone."

The film was safe.

"After that I told the police exactly what we'd done, and the university let us off! They just wanted to check it out but that was that. Part of the fun of making the movie. That's all."

And when Jack Nicholson has fun, it seems to be very contagious.